For Father’s Day this year, I received an interesting gift from my step-daughter – an ancestry testing service that analyzes genetic markers in a person’s DNA to determine the likely geographical origins and heritage of their ancestors. All I had to do was spit into a tube and mail the sample to the lab. Two weeks later, a report of my genetic analysis was available for me to view online.

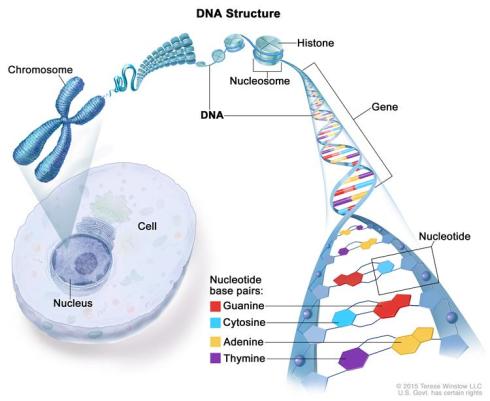

The science behind Genetics is complex and can be hard to grasp for the average person. In school we learned that all life is made up of cells and that inside those cells long strands of DNA molecules are compacted into thread-like structures called chromosomes. Human cells have 46 chromosomes, 23 inherited from the mother and 23 inherited from the father.

Image courtesy of National Cancer Institute

Located on the chromosomes are genes. Genes are molecules that act like instruction manuals in our body. Each cell in our body contains over 20,000 genes. Working together, these genes describe specific biological codes that determine which traits we inherit from our parents (like eye-color, nose shape, height and even behavior) .

Scientists tell us that the genetic code that are part of the DNA and RNA molecules inside all living organisms contains compelling evidence of the shared ancestry of all living things. Higher life forms evolved to develop new genes that support different body plans and types of nutrition – but even so, complex organisms still retain many of the same genes from their primitive past.

Prior to having my DNA tested, my understanding of my ancestry did not go back very far. I knew only that my maternal grandparents were farmers who had emigrated from Canada to the United States in the early 1900’s and that my father believed his ancestors emigrated to America from Wales sometime in the 18th century.

I admit to a slight feeling of trepidation as I dropped my sample into the mailbox. I wondered what the possible side-effects of exposing the secrets of my genetic past could be – and how it might be risky to pull up rocks from time gone by when you can not be sure what may crawl out to bite you. Thinking about the words of the philosopher Edmund Burke who wrote: “People will not look forward to posterity, who never looked backward to their ancestors“, I pushed any concerns aside and mailed my sample.

Luckily, the results of my look backward in time were mostly in line with what I expected to find and only revealed a few surprises that made for interesting conversations with my family. According to the lab report, the DNA in my saliva had this to say about me:

- My most recent ancestors all came from the European region.

- I am 41.1% British & Irish, descended from Celtic, Saxon, and Viking ancestors. I most likely had a great-grandparent who was 100% British & Irish. This came as welcome news to my lovely lass Kathleen who was happy to learn that I shared some of her Irish heritage.

- I am 38.7% French and German, descended from ancient Alpine-Celtic and Germanic populations that inhabit an area extending from the Netherlands to Austria. I most likely had a great-grandparent, born between 1870 and 1930, who was 100% French & German.

- I am 3.8% Scandinavian, descended from the people of Norway, Sweden, Denmark, and Iceland. I most likely had a third, fourth, fifth, sixth or seventh-great grandparent who was 100% Scandinavian and born between 1690 and 1810.

- My maternal line stems from the genetic branch T2a which traces back to a woman who lived nearly 17,000 years ago in the Middle East. Her descendants spread over the millennia from its birthplace in the Middle East to northeastern Africa and throughout Europe, riding waves of migration that followed the end of the Ice Age and the origin of agriculture. 1 in every 490 people share this common ancestor.

- My paternal line stems from a genetic branch called R-M269, one of the most prolific paternal lineages across western Eurasia. R-M269 arose roughly 10,000 years ago, as the people of the Fertile Crescent domesticated plants and animals for the first time.

- King Louis XVI and I have a common paternal ancestor who lived 10,000 years ago.

- Jesse James and I have a common maternal ancestor that lived 19,500 years ago.

- 244 Neanderthal variants (4% of my total) were detected in my DNA. This information will come in handy for those times when I try to explain to my wife the reasons behind my sometimes boorish behavior. Neanderthals were ancient humans who interbred with modern humans before becoming extinct 40,000 years ago. Fortunately, I have inherited a known Neanderthal variant associated with having less back hair.

The results that surprised me the most were the revelations of my Irish, German and Scandinavian heritage (which I was not aware of), my ancient ancestral connection to King Louis the XVI and Jesse James and the existence of Neanderthal variants in my DNA.

Those revelations were interesting, but surprisingly, the two biggest things I took away from this ancestry research activity are that: 1) more things unite us than divide us; 2) genetics is not destiny.

There are more things that unite us than divide us

Throughout history, humans have consistently focused on the ways that we are different. People have been categorized, judged and assigned value based on the color of their skin, their physical attributes and their culture.

But when you look at people through the lens of genetics, all humans basically belong to the same family. Our bodies have 3 billion genetic building blocks that make us who we are; yet only a tiny amount are unique to us, which makes all humans about 99.9% genetically similar.

To put this into perspective, physicist Riccardo Sabatini pointed out in his TED talk that a printed version of your entire genetic code would occupy some 262,000 pages, or 175 large books. Of those pages, just about 500 would be unique to us. The genetic book of any two people plucked at random off the street would contain the same paragraphs and chapters, arranged in the same order. Each book would tell more or less the same story. But one book might contain a typo on one page that the other lacks or may use a different spelling for some words.

We’re mostly just all the same. But instead of embracing our genetic similarities, we cling to small visible differences as symbols of what makes us unique. How silly it is for us to carry racist or prejudiced beliefs that some people are somehow born superior to others.

An observation made by the character Susan Ward in the novel I am currently reading (“Angle of Repose” by William Stegner) points out how people can benefit when they keep an open mind, accept others and embrace diversity. Susan was raised as an elite intellectual in high class New York society. She went out to the Wild West after the Civil War to join her engineer husband who was surveying the Western lands. In an 1884 letter to her friend back east, Susan Ward wrote this about the Chinese cook they employed in their camp:

“When I first moved out here the sight of a Chinese made me positively shudder, and yet I think we now all love this smiling little ivory man. He is one of us; I believe he looks upon us as his family. Is it not queer, and both desolating and comforting, how, with all associations broken, one forms new ones, as a broken bone thickens in healing.”

Humans also share a remarkable amount of genetic similarities with all living things. This is because large chunks of our genome perform similar functions across the animal kingdom.

All life on Earth is related and shares a common ancestor. We are about 99 percent the same as our closest animal relatives, the chimpanzees. Humans, mice and many other animals shared a common ancestor some 80 million years ago; and humans and plants share many common genetic traits associated with growth, sexual reproduction, respiration and the need for water, oxygen, and other chemicals.

Knowing that all life is related in this way gives us reason why we ought to be respectful of life in all its forms.

Genetics is not destiny

The second thing I take away from this activity is that Genetics is not destiny. I understand that our genetic makeup has a big influence on how we develop and behave; and that “mistakes” that occur during genetic replication will hurt some people (by causing disabilities and diseases) and help others by increasing longevity. In a universe of blind justice there is no satisfactory explanation as to why certain people inherit “good” or “bad” genetic traits.

Beyond genetics though, our destiny is influenced in large part by the environment we were raised in and the choices that we make. It is possible to overcome unfavorable genetic natures if, while we are growing up, we are nurtured in a safe and supportive environment with access to adequate nutrition, education, and health care and we have respectful role models and mentors to help guide our steps .

Psychologists have long debated this “Nature vs Nuture” question. Some argue that nature is the greatest determining factor while others argue that nurture is more important in determining how we will turn out. Most now agree that it is a combination of both.

Knowing that all humans share 99.9% of their genetic code, it makes sense to me that the differences between people are more related to their environment than their genetics. Everybody’s genes are basically the same, but we are all have different experiences in how we were raised which can have positive or negative effects on our brain development.

It is comforting for me to think that we have a chance to change kids for the better simply by treating them better. That is something that we can each control – we can always strive to continue making improvements in our behavior and our society’s treatment of children; but we can’t change the genes we were born with.

The reason I initially undertook this genetic testing activity is because I was interested to know who I was and where my ancestors originated. In truth, the information I learned hasn’t really enlightened me that much about who I am or what path I should take in life.

What I really learned is that the most we can say about DNA is that it governs a person’s potential strengths and potential destiny. However, we mustn’t allow ourselves to be chained to blind fate or ruled by our genes. We must remember that despite our genes all of us have free will and can choose the type of life we want to live.

Leave a comment