The picture of human nature painted by Princeton Professor and science journalist Robert Wright in his book “The Moral Animal: Why we are the Way We Are – the New Science of Evolutionary Psychology” is not a very flattering one.

According to Wright, the human animal spends its life desperately seeking status because we crave social esteem and the feel-good biological chemicals that flood our bodies when we impress people.

Though we claim to be independent thinkers who hold fast to our moral values no matter what the consequences, the reality is that we become self-promoters and social climbers when it serves our interest.

What generosity and affection we bestow on others has a narrow underlying purpose, aimed at the people who either share our genes or who can help us package our genes for shipment to the next generation.

We forge relationships and do good deeds for people who are likely to return our favors. We overlook the flaws of our friends and magnify the flaws of our friend’s enemies. We especially value the affection of high status people and judge them more leniently than strangers. Fondness for our friends tends to wane when their status slips, or if it fails to rise as much of our own and we justify this by thinking “He and I don’t have as much in common as we used to“.

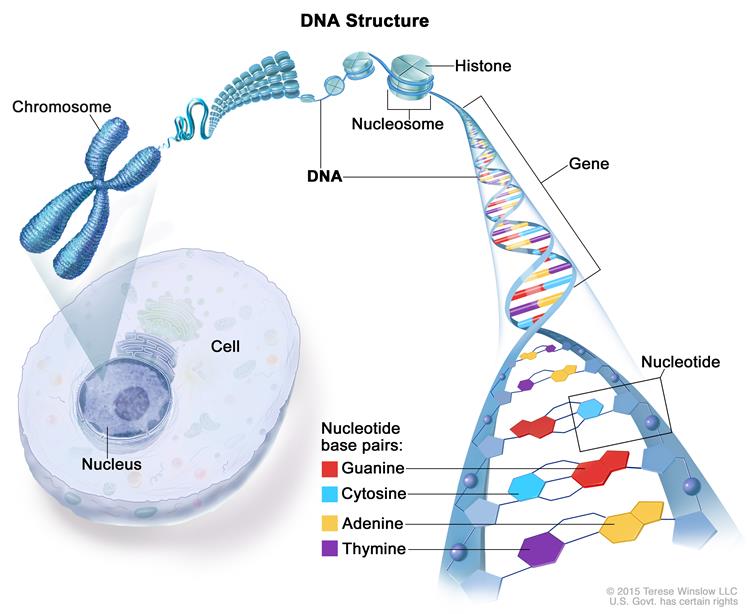

Wright says that we do all these things, mostly unconsciously, because of the evolutionary roots of human behavior that have been passed down throughout the 2 million year evolution of the human species – these behaviors are programmed into our genetic molecules.

The book explores many aspects of everyday life while looking through the lens of evolutionary biology. It borrows extensively from Charles Darwin’s better-known publications (including On the Origin of Species) to provide evolutionary explanations for the behaviors that drive human social dynamics.

Below are just a sample of the provocative questions Wright tackles in his book:

Why are humans more monogamous than other animals?

The birth cycle of the human species, unlike most animals, takes a long time. Human mothers carry their babies for 9 months and their children require years of caring and development before they are capable of living independently.

Due to the long birth cycle, women only have a limited number of chances to pass on their genes to the next generation (about a dozen or so during their lifetime). Men, on the other hand, have unlimited chances to pass on their genes given enough supply of women.

From a male evolutionary point of view it makes sense that their genetic drive would be to have sex with as many females as possible. However, this is not in the best interest of the female. To increase the chances of survival, and the well being of her children, it was in the female’s best interest to select male partners who were high in a genetic trait that Wright calls “Male Parental Investment“. Men with high parental investment traits have loyalty characteristics that make them more likely to invest in a monogamous relationship with a single woman and their children.

Men who women perceived were more likely to stick around after their baby was born became more appealing to women and therefore more likely to successfully mate with them. As a result of this preference by females, the trait for high male parental investment evolved over time to become more genetically prominent in men across thousands of generations.

Why is a wife’s infidelity more likely to break up a marriage than a husband’s?

Jealousy is a natural emotion for human beings, but a 1982 experiment which asked participants to picture their partner either having sex with another person or forming a close emotional bond surprisingly showed that men and women experience jealousy very differently.

For the men, picturing their mate having sex with another person led to feelings of intense rage and anger while the idea of their mate being close friends with another male didn’t bother them as much. Women, on the other hand, showed the opposite reaction. They were much more distressed with the idea of their partner forming an emotional attachment with another woman than they were with the idea of one-time sexual infidelity.

Wright attributes both of these responses to a natural built-in evolutionary reflex of the human species. It is the male’s unconscious desire to propagate their genes that drives their sexual jealousy. Picturing their partner in a sexual act with another man was enraging to them because of the possibility that another man could impregnate their partner, potentially resulting in them rearing a child that had another man’s DNA.

For females, it is not so much the thought of their mate having sex with another female that is upsetting to them; it is the danger that her mate will form an emotional bond with another woman and it will lead to him withholding some of the resources that her man provides to her and her children (so that he can share them with the new woman).

What makes a family prefer some children over others?

Wright claims that evolution has a role in influencing which child and specifically, which gender children the family prefers. Evolutionary psychologists explain that parents will tend to favor the child/gender that has the greater potential to carry on their family’s genes.

This ability to pass on genes historically differed based on what social class the family came from. In a poor family of low status, it was usually the girl who had a greater chance to marry “up” into a family that was wealthier. In wealthier families, it was the boys who were favorites to spread their family’s genes because of their power to find any woman or even multiple partners.

In a study of medieval Europe and nineteenth-century Asia, anthropologist Mildred Dickeman reported that killing females before their first birthday, was much more common among rich, aristocratic families than it was among poor and low-class families. And rich families much more frequently gave inheritances to their eldest son rather than their eldest daughter.

This evolutionary influence still carries on today. A 1986 research study of the island families in Micronesia found that low-status families spent more time with their daughters while higher status families spent much more time with their sons.

Why do humans have morals?

Why is it that humans seem to exhibit a higher sense of morals than other species? Is it because we are conditioned to do what’s right from a very young age, or is it something we are born with? If you ask an evolutionary psychologist, they’ll say that humans behave in a moral way simply because it helps us to fulfill unconscious Darwinian urges for the survival and propagation of our species.

Our moral behavior is an evolutionary instinct from our past that helps us to survive while enhancing our image. In essence, doing good things for other people is to our advantage because it establishes a debt in our favor that we can cash in at a later date when we need help. For example, if you give food to someone who is desperately hungry, they are much more likely to assist you in the future when you need help to survive.

Wright refers to this concept as “reciprocal altruism“. Our altruism is not selfless. We will readily do good things for other people when it will improve our image and standing in the community or raise our overall social status.

On the other hand, we are not so quick to help others when doing good for others carries no benefit to us. It is clear that human moral sentiments are used with brutal flexibility, switched on and off in keeping with our self-interest.

Evolutionary Psychologists conclude that there is scientific evidence that what we do can be explained by the evolution of our species and the unconscious urges we have to pass on our genes. Altruism, compassion, empathy, love, conscience, the sense of justice — all of these things, the things that hold society together, the things that allow our species to think so highly of itself, can be shown to have a firm genetic basis.

That’s the good news. “Given that self-interest was the overriding criterion of our design, we are a reasonably considerate group of organisms”, says Wright. The bad news is that, although these things are in some ways blessings for humanity as a whole, we need to keep in mind that they didn’t evolve for the “good of the species” and aren’t reliably employed to that end.

Although I found this book thought provoking and many of its insights fascinating, I still like to believe that we are more than just animals doing things instinctually or robots running a program that was downloaded into us. I believe we are all endowed with a spirit that makes it possible for us to rise above our nature and resist the urges of what Biologist Richard Dawkins calls our “selfish genes”.

In the movie “The African Queen“, there is a scene where Humphrey Bogart claims that he can’t change his bad behaviors because “it is only nature”; but Katherine Hepburn responds smartly to the captain’s statement by saying: “Nature, Mr Allnut, is what we are put in this world to rise above.”

May you experience all the benefits and wonder of our miraculous genetic past, but also have the strength of spirit you need to overcome our built-in selfish instincts and motives. If you can do this you will become more than human!