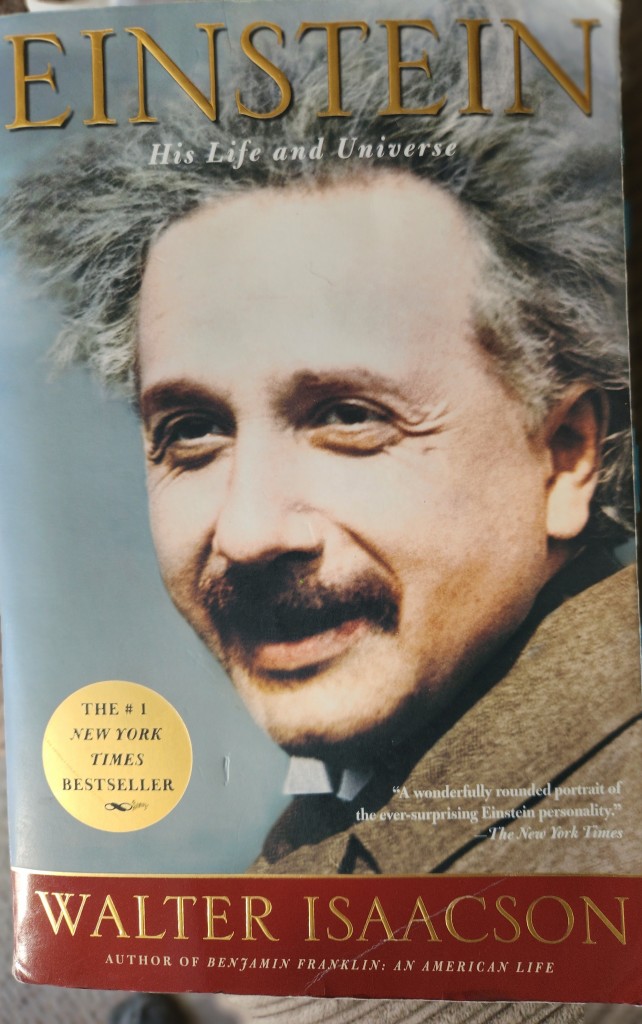

This summer I read Walter Isaacson’s illuminating biography of Albert Einstein, the man who is widely considered to be the greatest thinker of the 20th Century. In 1905, when he was only 26 years old, he published four groundbreaking papers that forever changed the way people understood space, time, mass, gravity and energy.

By the time Einstein turned 40 in 1919, at a moment when he was struggling to devise a unified theory of matter, he complained to a friend that “Anything truly novel is invented only during one’s youth. Later, one becomes more experienced, more famous – and more blockheaded“.

Einstein’s frustration at his diminished capabilities as he aged is a phenomenon that is considered common with mathematicians and physicists who seem to make their greatest contributions to science before they turn 40. Einstein remarked to a colleague that as he got older he felt his intellect slowly becoming crippled and calcified.

Why does this happen? In Einstein’s case, it was partly because his early successes had come from his rebellious traits. In his youth, there was a link between his creativity and his willingness to defy authority and the universally accepted cosmological laws of his day. He had no sentimental attachment to the old order and was energized at the chance to show that the accepted knowledge was wrong or incomplete. His stubbornness worked to his advantage.

After he turned 40, his youthful rebellious attitudes were softened by the comforts of fame, renown, riches and a comfortable home. He became wedded to the faith of preserving the certainties and determinism of classical science – leading him to reject the uncertainties inherent in the next great scientific breakthrough, quantum mechanics. His stubbornness began working to his disadvantage as he got older.

It was a fate that Einstein began fearing years before it happened. He wrote after finishing his most groundbreaking papers: “Soon I will reach the age of stagnation and sterility when one laments the revolutionary spirit of the young“. In one of his most revealing statements about himself, Einstein complained: “To punish me for my contempt of authority, Fate has made me an authority myself“. He found it even harder as he got older acknowledging “the increasing difficulty a man past fifty always has adapting to new thoughts”.

Einstein brilliance is beyond compare, but I can relate to his observation about doing your best work when you are young. When I look back at my personal life and work career, I recognize that I was at my most ambitious and innovative during the decades of my 20’s and 30’s.

My adult life exploded with big events in 1982, the year that I turned 22. In the timespan of that one year I managed to graduate from college, marry my college sweetheart, start my first professional job as an engineer, buy a new house and a new car, and learn that my wife and I were going to become first-time parents. I remember filling out a survey designed to measure the amount of stress in your life during that eventful year and being surprised when the calculated stress numbers registered so high that they indicated I should be dead!

But all of it was exhilarating to me at that point in my life. I was experiencing new things and accumulating knowledge like a sponge. I knew that my growing family would be counting on me to be a good provider – which gave me the incentive I needed to focus on building a stable career.

I was determined to be successful in my engineering role and threw myself into learning everything I possibly could about the company I worked for as well as the electronic test and measurement equipment that they manufactured.

Many of my co-workers had graduated from more prestigious universities than me and I felt that I had something to prove. I wanted to make a name for myself and grow my reputation and value within the company by making important contributions to the projects to which I was assigned.

I took several continuing education engineering classes at night to improve my knowledge of subject areas that I knew would be helpful to me at work, I sought out brilliant co-workers who could mentor me and give me wise advice on how to approach complex technical projects, and I questioned everything – wondering if there might be a better solution to the problems we were trying to solve.

This drive in my early career to be successful enabled me to do my most innovative and important work for the company during the decades of my 20’s and 30’s. In the span of my first 18 years working for the company, I was awarded two patents, helped develop multiple new test products which generated millions of dollars for the company, created automated software regression tests significantly lowering product development times while improving software quality, and published frequent technical articles for industry conferences and trade journals.

By the time I turned 40, I could point to many important career milestones and had achieved recognition as a top performer and leader within the company. The rewards of my hard work were a comfortable home and financial independence. With this success I began to have feelings of contentment that lessened my drive to take on new projects or solve interesting problems. I became comfortable and happy with life as it was – I no longer felt the need to over-extend myself.

I was satisfied to rest on my past achievements and to take on less tasking roles that would improve the product in evolutionary, rather than revolutionary ways. Over time, I became the wise, experienced, older mentor to younger employees who came to me for advice and direction.

I felt okay with that transition as I considered it my good fortune to be in a situation where I was able to share my knowledge with a new generation of ambitious young people who were ready to make their own marks on the world by inventing novel new solutions that were now beyond me. In some ways, being a part of those collaborative efforts made me feel better than my individual personal accomplishments.

The famous journalist Ed Bradley once interviewed Bob Dylan in 1998 on the television show 60 minutes, at a time when he was approaching 60 years old. During the course of the interview, Bradley asked Bob what the source of inspiration was for his famous early songs, the ones that led to him being recognized as the voice of a generation while he was still only in his 20’s.

Dylan replied that his early songs were almost magically written and that he felt some kind of power, outside of himself, flowing through him while was writing them. When Bradley asked if he could still tap into that penetrating magic now in his songwriting, Dylan paused and said; “No, I don’t know how I got to write those songs“. Bradley followed up and asked if that disappointed him, Dylan replied softly; “Well you can’t do something forever and I did it once… and I can do other things now – but I can’t do that“.

That is a healthy way, I believe, of thinking about what is possible for each of us as we age. My days of endless ambition and innovative thinking are past. But I can do other things now that I couldn’t do then. I can indulge hobbies that interest me, I can find new paths to hike and rivers to fish, I can help care for my mother in her old age and I can share what I have learned through my life experiences and pass it on to my grandchildren and the larger community via this blog.

There will only ever be one Einstein, none of us will ever be as brilliant as him – but if you are under 40, get busy by putting your spry young mind and youthful ambition to work! Maybe you too can come up with novel ideas and ways of doing things that will help change the world or someone’s life for the better.

And if you are over 40, you can be like Einstein in his older years; contributing in a positive way to his community and sharing his wisdom, experience and good fortune with the next generation. In the end, many of our late in life pursuits that we share with others can end up being more rewarding and meaningful to us than any personal accomplishments we achieve along the way.